Our guest blogger, Cameron Wilson, is a member of our Library’s Collection & Discovery team. Cam joined us for a two week project working with the Scottish Marxist. Here he gives us his personal reflections on its value as a primary source.

“The function, as it seems to me,

O’ Poetry is to bring to be

At lang, lang last that unity…”

- Hugh MacDiarmid

As part of my library assistant graduate trainee program at Glasgow Caledonian University’s Sir Alex Ferguson Library, I was afforded the opportunity to intern in the library’s archive centre for two weeks. This internship has involved working with one of the most rewarding and valuable pieces of print media I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading – Scottish Marxist. For these two weeks I have worked on a comprehensive index of Scottish Marxist’s political articles, arts and culture articles, and original illustration and poetry.

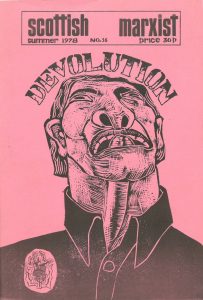

This run of Scottish Marxist, the official journal of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB)’s Scottish Committee, encompasses 26 issues running from 1973 to 1985. Printed in Glasgow, its 26 issues are 30 to 50-page, colourful booklets with illustrated covers that blend Marxist analysis of current events, historical articles on leftism and the trade union movement in Scotland, art and culture news, and original illustration and poetry. Scottish Marxist provided a unique and sorely missed print publication to Scotland’s leftist community.

Front cover of ‘Scottish Marxist’ Issue no.16, 1978

From my point of view, what made Scottish Marxist special and valuable was its focus on the arts. Both political analysis and original poetry and illustration are given equal precedence on these pages, they share both a physical and intellectual space. In a time when physical space for text came at more of a premium, that is, without ample digital space, deciding to afford room to original art and poetry, as well as articles about and interviews with poets, on the pages of a noteworthy political journal is extremely significant.

All art, and revolutionary poetry in particular, has always and will always play an important role in leftist politics. According to Ernst Fischer, “under capitalism…all art above a certain level of mediocrity [is] always an art of protest, criticism and revolt.” While much of the poetry in Scottish Marxist is explicitly political – making direct reference to matters of class, poverty, and Marxism – much of it is subtler in its cultural and political criticism. These poems often describe life or brief encounters in Glasgow – but lives and encounters coloured by poverty, social inequalities, or class differences. This kind of poetry is vital to the unity that poet Hugh MacDiarmid longs for poetry to provide, and publishing it in political journals such as these is vital to the slow but essential cultural change required of Socialism, that Lenin described as requiring “the maximum of perseverance, persistence and method.”

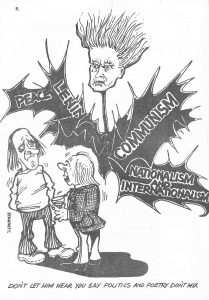

Issue no. 10 of Scottish Marxist contains two valuable pieces that really showcase the blend of art and revolutionary politics that this journal consistently provides. The first is an in-depth interview with Hugh MacDiarmid. MacDiarmid himself stood as a parliamentary candidate for the CPGB in 1964, and is one of the most influential Scottish writers of the 20th Century. In this interview he discusses his own work, his influences, and his views on poetry and politics in Scotland at the time of publishing – 1975. MacDiarmid is asked to speak about the commonly held view that his own poetry, and poetry in general, is elitist and “too difficult.” Perhaps surprisingly, MacDiarmid responds by doubling down, stating in fact that making poetry less ‘difficult’ would be making a “concession to illiteracy,” which is “not due to any lack of inherent ability in the people, [but] due to the kind of society in which we’ve been living and are still living.” This attitude is reflected in Scottish Marxist itself, which unapologetically includes material which is still commonly seen as inaccessible and elitist in 2022 – poetry, the arts, and Marxist analysis. This journal makes no assumptions about the ability of their readers to effectively interpret their content. In fact, by consistently publishing such a wide variety of both creative and political material, I feel that Scottish Marxist actively encouraged its readers to keep an open mind and engage with pieces that were perhaps out of their comfort zone.

This is further highlighted by the subsequent article in issue 10, ‘MacDiarmid’s Language’ by Bill Sweeny – a detailed poetic and political analysis and criticism of MacDiarmid’s use of Scots in poetry. In this article, Sweeny emphasises the significance of MacDiarmid’s poetry to the wider working-class movement in Scotland, stating that “MacDiarmid is not, and never had been, only for artists, poets and the like: it’s for us all (that is, those of us interested in progress).” The final section of this article again echoes the role of Scottish Marxist in the political sphere, that being to emphasise the intrinsic and essential relationship between leftism and the arts in Scotland. Sweeny encourages us to create works that include the common speech of the working-class, and create images that reflect social reality in Scotland, knitting together working-class ideology and the working-class movement.

Artwork by ©Bob Starrett from Scottish Marxist’ Issue no.10, 1975

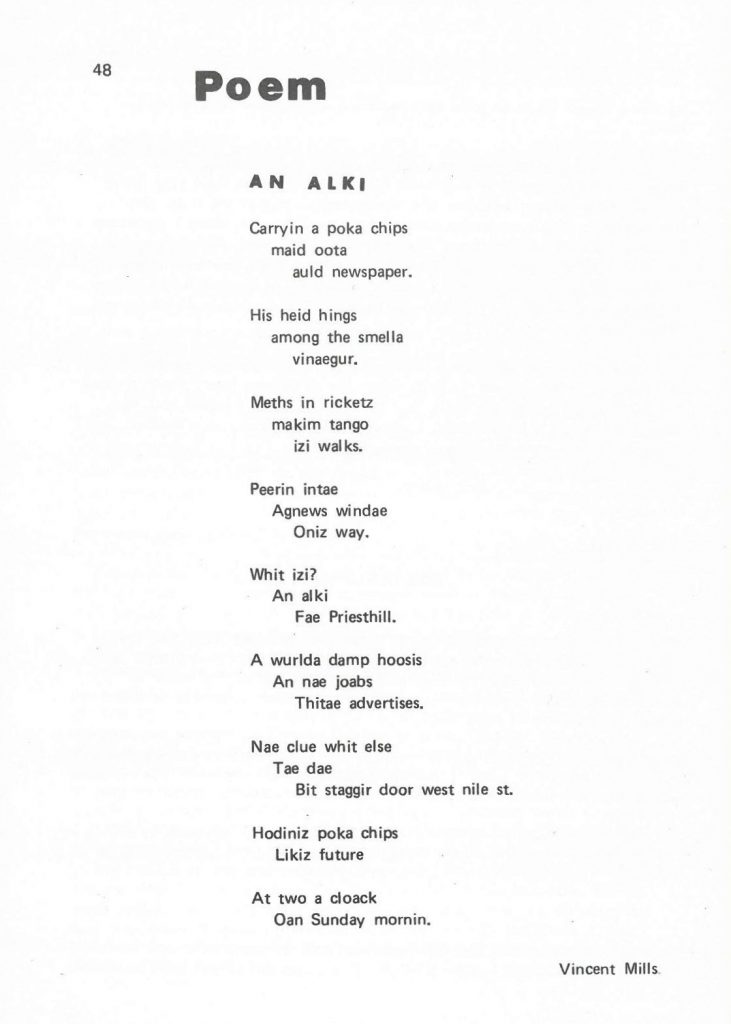

Examples of precisely this kind of poetry and art are strewn throughout these issues of Scottish Marxist, be they the political cartoons of Bob Starrett, or poems written by journal contributors. Starrett, a life-long trade union activist and artist, contributed numerous political cartoons to the pages of Scottish Marxist, with themes ranging from miners strikes, landownership, and nuclear weapons to theatre closures, North Sea oil, and unemployment – themes and images which certainly combine the working-class movement and ideology. One of the poems within these pages that carries that same ethos is found on page 48 of issue 13 – An Alki by Vincent Mills. Written entirely in colloquial Glaswegian dialect, this poem pushes the language to its limit by using non-traditional Scots spelling, effortlessly communicating to the reader the struggle of the working-class Glaswegian alcoholic in both its sound and imagery. Mills creates completely original compounded words such as “hodiniz” (haudin’ his), “izi” (as he), and “wurlda” (world of), creating sounds deeply familiar to the working-class Glaswegian. It is precisely this kind of poetry, this style of language, reflecting the social reality of the working-class, that fosters a unique environment within the pages of Scottish Marxist. An environment that was infinitely valuable to the working-class movement, and contributed to the unity that MacDiarmid longed for, that he knew poetry could provide.

Poem by ©Vincent Mills from ‘Scottish Marxist’ Issue no.13, 1977

I implore you to read and enjoy this archival material. Scottish Marxist has widened my view of Scottish leftism in the late 20th century, and highlighted a powerful ethos that holds deep value for the working-class movement, 50 years on in 2022.